Tuesday, 8 June 2010

Inside ME?

Michael Winterbottom has been a film-maker that I have admired for a long time. I enjoyed

Wednesday, 19 May 2010

Allegories

Having now seen Robin Hood, I realised how much it was an allegory of our time. There's trouble with the economy because the king is fighting a war on foreign lands. It's pretty straightforward. This got me thinking about the Hollywood industry and its history with allegories - nothing new, and certainly elements of blockbuster films, (and of course, science fiction) have always had elements that resonate to their time. What did intrigue me, however, was the swing in style of allegories since September 11th 2001 that have emerged from the Hollywood system. I am hoping to explain this change, exemplified by several blockbusters of the past 15 years, and show that the Hollywood system has reflected the political, and ideological trend of (particularly) the USA. The films are -

Independence Day (1996, 20th Century Fox)

Godzilla (1998, Tristar Pictures)

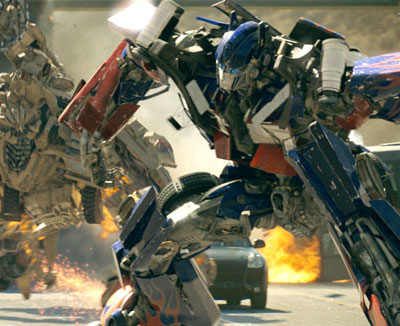

Transformers (2008, Dreamworks)

2012 (2009, Columbia Pictures)

The aim of this piece is to spot the shift both in plot and ideology from the films pre-September 11th to those that are more recent. While there are, obviously, films that may not fully conform to this (Nicolas Cage's output in the 90s particularly seems to be more introverted.) there is certainly the sense that the mid to late 90s showed a sense of America's output to other countries, to show America as peacekeepers of the world.

More recent films, however, have emphasised America's inability to both prevent, or control, attacks from foreign films. While it is 2012 that will be discussed, certainly Emmerich's other output, The Day After Tomorrow not only conforms to this, but also plays into 2012's fear of global catastrophe - however, it places the blame of this upon the world's shoulders - another level of allegory.

The aim therefore, is three fold - Firstly, I will explain how, briefly, and without dwelling in detail, on the effects of September 11th on America - much of this from my own experience (I lived in America from 1999-2002, and visited New York both in July 2001, and 2002.) I am not intending this to be comprehensive, and will be the first to state that there is much writing on this already - in fact, much of what I discuss is based on Dixon's Film and Television After 9/11. Secondly, I will aim to show how both Independence Day and Godzilla demonstrate a pro-American point of view; one that is specifically focused on America's ability, both as a community and ideologically, to 'solve' the world's problems. These are problems that - like films post September 11 - are not America's fault, but ones in which America finds the way to fix.

Finally, I will show how films after September 11th, particularly, Transformers and 2012 represent a post 9/11 view, one of more hopelessness, one of survival, and one in which American ideals, whilst not sidelined, are shown as not fully effective at solving the problems of the diegetic worlds.

Pre September 11th, it could be argued that America saw itself as 'invulnerable' and a country of ideals that were not questioned, ones that held democracy and strength as hallmarks of its Nation. Films, therefore reflected this trend to strength - the American Hero, the ideals of truth, freedom and democracy seen as ones that should be held throughout the world.

It may be argued that this could be seen as 'cockiness' by other countries, however, it was certainly one that put an emphasis on America's achievements.

After September 11th, one of the strongest feelings in my immediate circles of friends was one of shock, that America could be seen as a target, that someone would 'dare' to attack it. This immediate feeling of weakness certainly translated into a feeling of humbleness, something I personally witnessed on a trip to New York, where the once brash, loud citizens of the city transformed into well mannered, quiet people. Something certainly changed in the country. While once, America could be seen as a bastion of ideals that the world should follow, post September 11th, these ideals changed, and could be questioned.

This piece is certainly not a critique of American politics, and I do not wish to dwell on them too long. However, the clear shift in attitude of the country as a whole must be taken into account before examining the following texts.

Pre 9/11.

Both Godzilla and Independence day share the same ideal around their central conflict. This is that the problems of the film are not created by America. While the films post Sept 11 are also of foreign origin, it seems more important that the 'villains' of the pre 9/11 films are worth examining. In Independence Day, it is blatantly, the aliens, those that have no concept of human (read - American) democracy. They invade without warning, they pose ominously over the most important cities of society, without reason, and without (so it seems) motive. It is this lack of motive that is most interesting. There is no reason to attack America (or, of course, the other cities in the film, but America is where it focuses). There is no complaint with America's politics, its policies, or its ideals, or indeed its people. There is a simple enemy that, with its lack of reasoning, or its ability to communicate with its nemesis, represents everything that can be seen as anti-American.

More than this, the hero that actually manages to save the world is (what can best be described as) John Q. Everyman - a 'white trash' trailer bound American, one who represents the best of America - individual, deeply heroic, family oreinted, despite his outward flaws. And he destroys the ships with a WW2 era plane.

Finally, the last important aspect to examine is the seemingly flippant line at the end of the film -

"Get on the wire, tell them how to bring those sons of bitches down."

Effectively, this is America using its own knowledge and experience to influence the rest of the world. The following montage of world cities, utilising the American Way to tear down the alien ships conforms to this idea - that America and its ideals are the way to deal with conflicts, and that they will not only deal with, but triumph and restore an equilibrium to the world.

Godzilla, while set in the US, is interesting in its concept - that the enemy was created on this planet - by the French. By radiation. And it then attacks Japanese ships. There is surely some sort of re-writing of WW2 history here. Perhaps the most galling concept is the idea that a radiation attack upon the Japanese was not in anyway influenced by the Japanese. Indeed, America in many ways disowns its own history of nuclear attacks, claiming that it would not dare to release such attacks. This is emphasised by Matthew Broderick's Dr. Niko character (someone channelling the mish-mash of cultural identities that ultimately created America) who constantly chastises the attacks throughout the film.

Once again, however, it is the Americans that 'solve' the problem and bring down the creature, not of their own making, this preventing it from attacking any other nation. Again, it is a combination of the American miliatry and an individual American 'everyman' that bring the creature down. And once more, it is the case that America, and its multicultural, intelligent democracy can fix problems of not only its own country, but of others.

Post 9/11.

It is perhaps remiss to mention Pearl Harbour - one of the last films to be released prior to 9/11. While America is indeed attacked in the film, there is not (despite fleeting *less than 1 min sequences*) any reason to empathise or explain the Japanese motives for the film.

Post 9/11, films such as Spiderman, Zoolander etc changed their landscape and sequences. Spiderman, most explicitly, ended with an American Flag in full view as Parker reached his potential, the innocent, attacked individual rising up against the pressures of the outside world. Whilst this is certainly a trend of films, it is interesting to examine the idea that films have more reflected the concept that America is not immune from the horrors of the world.

Transformers perhaps best exemplifies the post 9/11 mentality. This is most apparent in its Army/Marine storyline. The men are seen as out of their comfort zone, and ones who, whilst manage to adapt to the situation around them, are out of their depth, and ultimately unable to influence the actual events of the film.

Once more, aliens attack the world. Unlike Independence Day, however, the US does not manage to resolve the issue - they are unable to even deal with the concept. In fact, one of the key emotional sequences involves the 'unfair' capture of one of the 'good' aliens, perhaps referencing Guantanamo Bay style methods - in effect, criticising the very country that the film is created for. The army, whilst managing to survive, do not in anyway really influence the outcome of the film. This is the key idea that permeates post 9/11 film. That America is concerned with survival, and survival of its ideas against outside influences. The American ideals do indeed remain, but it is ultimately the Autobots that triumph in the film, and who end up 'protecting' the earth. America, in many ways is left with its 'pants down' (thank you, Turturro) against the alien outsider.

A far cry from Independence Day.

Finally, 2012. In my own memory, there has not been a blockbuster American film that has taken as many influences from as many other cultures as possible (obviously primarily Russian). Not only this, but the outside influence (that is not even human, but completely UNAVOIDABLE - a comment on terrorism?) is one that affects the whole world - perhaps explaining that any problem that affects the US affects the whole world. Does this then 'sell' America again in a manner similar to the pre 9/11 films?

While the protagonist of the film is once again American, his family is disintegrated (although he ultimately reunites with them) and is not the sole hero of the film. Indeed, the President of the United States is killed, as is Washington DC. Does this perhaps state that America now realises it is not the only nation in the world? That its ideals are not THE answer to society's problems?

Some may argue that blockbusters are unimportant in terms of filmic value. Far from this. As they need to endear themselves to the world, they need to reflect current world sensitivities, and push away from common world views. Consider the GI Joe film - a title shift away from 'Real American Hero', right?

Perhaps, for the next trends in current world view, we should look to the biggest films in the world.

Wednesday, 28 April 2010

The Past...

It's a widely regarded belief amongst theorists that Science Fiction films and novels speak more about the present than the future. Consider films such as Star Trek or 2001 that, in the age of space travel, pondered our own origins and existence on the planet. Coming at the end of the 60s, a period of (mostly drug inspired) reflection, these fit absolutely perfectly.

Or perhaps examine I,Robot, in gestation (pun?) since shortly after the announcement of Dolly the sheep. It's clear that these films reflect our times.

Is this restricted to Sci Fi? Do Horror films reflect our current fears? Cetainly in other countries they do, but primarily, in the West, we seek for our reflection in the future. Until now, that is. Step forward the Brits, I guess.

Or perhaps examine I,Robot, in gestation (pun?) since shortly after the announcement of Dolly the sheep. It's clear that these films reflect our times.

Is this restricted to Sci Fi? Do Horror films reflect our current fears? Cetainly in other countries they do, but primarily, in the West, we seek for our reflection in the future. Until now, that is. Step forward the Brits, I guess.

Centurion (2010, Celador Films)

Robin Hood (2010, Universal Pictures)

Hood is obviously not out in UK cinemas at the time of writing this blog, but it is an interesting time for a remake of this famous tale to be told. In the past two years, the UK (and the West) has been hit by a recession, the collapse of banks, of trust in government for many reasons. Is it a surprise that the story of a man striking against the rule, fighting for equality and striking back at the very rich has been made since this? Probably not.

There are several stories that have resonated throughout the age of cinema. Man vs. Technology is a fight that has existed since La Voyage De La Lune. The small man vs. the corporation has seen its form in many years, from Mr. Smith, through It's A Wonderful Life, through Soylent Green, to most recent outings such as Michael Mann's The Insider.

It is only logical that this be the time for a Robin Hood.

Centurion, on the other hand, is a little more subtle than Ridley Scott's film. But not much more.

Centurion recounts the famous Boys' Tale of The Eagle of the Ninth. Except, in his gloriously gory film, Marshall has chosen to add a modern day metaphor to his piece.

Consider the Romans - dominating foreign lands, but meeting stern resistance throughout Scotland by the indigenous people who utilise guerrilla tactics in order to maintain their hold on their country. The Romans are noble, brave, but are ultimately led by a foolish leader.

There are traitors within their organisation, and ultimately, the men in the company no longer care about their task, or the goal of their nation. They simply want to escape.

What on earth could this be related to?

It's not hard to see that Marshall has used the well worn tale as a modern metaphor.

What is most interesting about both these films is that they don't focus on looking forward in order to warn us of the problems that await our planet. They look back, and recognise that the mistakes that have been made in recent years, ones that we are all to keen to leap down our leaders' throats, are mistakes that all great empires, all nations have made in the past.

Perhaps the past can tell us as much about our lives as looking at the future can.

Tuesday, 20 April 2010

Take it back...

There's a particular strand of Japanese Horror that, unlike say the avenging spirits of Ju-On, Ringu, or the daikaiju eiga (giant monsters) of Godzilla et al, has never successfully translated well to Western audiences. Critic Jay McRoy calls it the techno/body-horror genre. While it is true that the genre has in some sense died out in its homeland, it is certainly something that has never been accepted in the West. In the US and UK, audiences are uncomfortable with their own bodies, let alone those of onscreen characters. Plastic surgery and fad dieting pervade life, yet confrontation disturbing the palace of the human body is something Western audiences shy from. David Cronenberg may indeed be the only real Western director to exploit this. Films such as the Saw series cannot truly fit this, as they focus on the perpetrator rather than the victim, and the consequences of the crimes committed are never REALLY shown on screen. In Japanese cinema, the victims ARE often the perpetrators, and they often have to live with the consequences of their 'boundary violations'. In the West, the Terminator will always die or sacrifice their life at the end of a film, a knowledge that they cannot exist in the natural world. In the East, they are cursed to do so, a reminder of humanity's tampering with the natural order of the world.

With all this in mind, it was with a certain excitement that I looked forward to the next film, and in displaying its Eastern influences, it certainly lived up to the techno/body-horror tag.

Repo Men (2010, Universal Pictures)

Primarily, the film seems to be a non-too-subtle metaphor for both the longer living human race, in the era of Dolly the sheep et al, and also the recent 'Credit Crunch' recession. The film seems to both rejoice and despise the mechanical additions to the human body in that they ultimately save the protagonists several times, but the 'black comedy' of the film seems to ridicule those families that do take the artificial organs, for what the film seems to insinuate are selfish means.

It will be interesting to see how (if?) a mainstream audience responds to this accusation, given that Western society is obsessed with staying young, and does not respect its elderly in the same way that Japan does. Can an audience accept a film that mocks them for wanting to stay young? Yet, this is not what fully divides Repo Men from traditional cinema. This 'knowingly subversive' style has been around for years, and it is not a stretch to say that Repo Men treading ground that Fight Club walked over a decade ago.

However, clearly, this is a film with a mixed message for its target audience. And who are they? It's hard to say. With a marquee Summer release for Japan, it's perhaps a film that will do better business overseas, where its Western-mocking stance may be easier to swallow. As a result of that, it takes influences from South Asia in various forms.

The film wears many of its influences on its sleeve. There's the obvious Asian fusion of the cityscape, in a Blade Runner manner, and the climactic fight sequence seems to be obviously inspired by its use of tools (including a hammer!) from another film on this page, Oldboy. This lacks the power of Oldboy's single take brutality, however, focusing on an UNKLE soundtracked fight more similar to something from the Wachowski's Matrix Trilogy. Most unnerving, however, is the finale of the film. It is here that the Cronenberg, and more disturbing aspects of body-horror are referenced.

Near the end, as the protagonists try to 'scan' items inside their own bodies, while cutting each other open, they begin to passionately kiss each other, ultimately literally kissing through the blood as (primarily Law) reaches inside stomachs, knees, chests, to scan organs.

Ian Conrich categorises this particularly odd combination as 'techno-eroticism', and states that the ultimate mating of two may ultimately result in the death of society. This was most literally shown at the end of the quintessential Japanese techno/body-horror - Tetsuo: The Iron Man, by the empty streets, as the fusion of men march through them, claiming they can destroy the world. It is perhaps a fear that by losing the organic nature of humanity, and ultimately replacing more and more of the body with technology, that we will one day be unable to recognise a human being.

Perhaps this is why Repo Men is unsatisfied with its ending.

Would an audience be content in seeing two protagonists, one more metal than human on the inside, together at the resolution of the film? Perhaps that's why Arnold always has to go at the end of the Terminator movies.

As long as technology continues, however, there's no doubt that, like this genre, he'll be ba...

.. No, I can't.

Wednesday, 31 March 2010

Got the job.

Audition. Not like my usual posts. I'm just saying what this post will be about. It's going to be about Takeshi Miike's Odishon (Audition.) The most shocking thing I watched during my time at university. I watched Mysterious Skin, Gozu, Visitor Q, Zombii, and so on. But Audition has stood in my head. Why? Is it the swift genre change? Is it the real horror of those last fifteen minutes?

Probably not.

It is more likely that my real fear and admiration of the film stem from what it actually says about both Japan and the Japanese. It is more of an acute eye upon their culture than any documentary could ever be.

So. Here goes.

Probably not.

It is more likely that my real fear and admiration of the film stem from what it actually says about both Japan and the Japanese. It is more of an acute eye upon their culture than any documentary could ever be.

So. Here goes.

Odishon (1999, Tartan Asia *UK*)

Takashi Miike has often stated that his films are not meant as social criticism. He has oft claimed that he yearns to show the darkness in humanity, the depths to which people may plumb in order to either create order or chaos. However, he is a Japanese director, and as such his films reflect a Japanese mentality upon this. Much as one would not expect Scorcese to create a South Korean epic (in fact, he adapted one!), apart from Eastwood, most directors stay to their homeland. Or, at least, a land that they can connect to.

Odishon is unashamedly Japanese, playing upon many of the conventions and idylls of Japanese society. Here is the housewife who is expected to be in her place, to be subservient to her husband. Indeed, the opening hour or so of the film is placed as thus. The opening sets up the idea that women in Japan are seen as having to adapt, or 'audition' themselves as something other than they are in order to maintain a man is ludicrous.

Yet this is a tenet that is still held in Eastern culture; that women need to attune themselves to their male counterparts.

In this sense, Odishon works as a mammoth wake-up call.

There is such a softness to the opening hour of the film, that this is another 'wacky' rom-com, almost in the sense of Richard Curtis, or numerous other rom-com creators. The very rich man has decided to share his fortune. As he is so rich, he is holding auditions for women who may meet HIS specifications. And the one who does meet such specifications does so magnificently.

They spend a curtain-blowing-indulgence of a holiday together.

Then Miike steps into the movie.

Takeshi Miike is a man who has made efforts to make POINTS in his work. He is oft at pains to strive points home that may not be accepted in his homeland, and here he shos how a female may stress their power upon a male.

In Western society this is not a major issue. For Japan, it is nigh treason.

The resulting actions that occur to Shigerhau are both graphic and (yes) treasonous to spoil. It is enough to say that is bride is not what she is made to be. But what does this say about Japan?

Most horror in Japan centers around one of two issues; either those of the body, or those of the female. The former has been widely covered in films such as Tetsuo, which look at how the body can be corrupted by technology. The latter is clearly shown in films such as Ringu or Ju-On.

So what does this say about Japanese culture?

Japan is terrified of losing its past - its body, as shown in the film by the literal removal of a body part. It is a culture in divide. Those pre-war and those post-war both have strong arguments as to what Japan means. What is the body of the country? Divided, as the movie suggests.

And then the role of women.

Miike is one of the forward thinkers in this culture, giving women full status, power over film, art. What of others? Takashi is pointing the way forward towards something more radical, a change in authority. An equality.

By foot, or by crook.

Monday, 29 March 2010

Alive and Kicking

The superhero movie has had a torrid decade. It's odd to think that it has only been ten-odd years since Raimi's Spider-Man relaunched a genre that was thought to have died along with nipple-Clooney. Spider-Man was a hero that was not sanctimonious, did not patronise his audience, or those around him. Superheroes were allowed to have problems, the same problems that you or I face on a daily basis. And it was cool. The resulting years saw some more hits, and many misses. Amongst these was Fantastic Four and its Silver Surfer sequel. These met with some hostility upon their release, and there are no immediate plans for Marvel to launch them. Yet, recently, some critics have come out recently, reappraising these as caught between the relaunch of the Batman franchise, and Spider-Man 3, surely one of the most teen-angst-y films of recent memory.

For a while, it was cool to be mopey, and if you had any fun in saving the world, you simply were not tortured enough to be a superhero.

Yeah, that's changed.

For a while, it was cool to be mopey, and if you had any fun in saving the world, you simply were not tortured enough to be a superhero.

Yeah, that's changed.

Kick Ass (2010, MARV Films)

Kick Ass, the 'big-independent film that could', is reversing the trend. As Mark Millar, creator of the franchise has stated, what he remembers about comics is the fantasy of dressing up and being a hero. Fun, in other words. Kick Ass is about as close to 'on-screen fun' as is possible.

This works on several levels. Let's start simply.

Comics, of the superhero variety, focus around a very simple premise - good versus evil. Yes, there are those titles that work in vague shades of grey around this, but ultimately the central concern is who is going to save the world (again.) Kick Ass is very clear about this. There is never any doubt about the heroes, none of Batman or Parker's moral ambiguity. Indeed, it's clear the that the 'hero' of the film is always going to, one way or the other, overcome the odds, and that evil will be punished. It's far less complex a plot than either Spider-Man 3, or The Dark Knight - indeed, the chief reveal of the movie is what weapon is inside that crate? And you know you're going to get to see it.

But wait, after The Dark Knight, surely any comic adaptation that works in simple colours will be lesser next to it?

Well, yes, and no.

The issue with The Dark Knight is that it's not really a comic book film. Indeed, the most laughable parts of the film are when the Batman character (characature?) shows up to break the mood of what is otherwise a Heat-esque thriller looking at a corrupt city.

In comparison, Kick Ass' best bits are when Nicolas Cage shoots everyone. In the face.

So that's the simple stuff dealt with.

What about the thorny issue of adaptation? Comic fans have historically had real problems with anything diverting from canon. Terry in Spawn - white? What? Sandman killing Uncle Ben? Huh?

These are areas where films have been made or broken. And this is where Kick Ass most benefits from having a sturdy, but hardly original film maker.

Matthew Vaughn's previous projects, Layer Cake and Stardust, have both been incredibly faithful adaptations from their source material. Kick Ass is no different (excepting one romantic angle.) Does this then make a comic film better - knowing how the story will end? Or should one expect to go in and experience a Watchmen-style change? Comparing reviews of the two films, it seems that the former is treasured. In this sense is the narrative of a superhero film different from those of others? Not particularly.

There is still the sense that Joseph Campbell's Hero's Quest pervades most modern single protagonist films. By their very nature, superheroes do not divert from this series of ordeals and challenges. Pleasure in the familiar? Why not. Plaisir, indeed. Or, let's simply say, fun in seeing something much loved in motion.

And so what of the 'deeper' level?

Kick Ass' real pleasure is in how it both lampoons and follows established comic-film tropes.

An example -

Both Peter Parker and Dave Lizewski test their newfound abilities on the rooftops, expecting that crossing buildings in a bound is a true signifier of power. It is crossing a threshold, for sure. Parker eventually manages it, resulting in a stunning tracking shot through NYC. Lizewski, well, he does what most of us would do when faced with the prospect of a suicidal jump across buildings, or sense prevailing. Yet, this doesn't mean the Lizewski doesn't later conquer heights or space. It's only in a... different manner.

And finally, there are the references to those films or heroes loved before. Most notably, Cage's Big Daddy is a shade of grey away from receiving a plagiarism lawsuit from Bob Kane. Pushing it even further, his superhero delivery superbly parodies the much loved Adam West, adding another layer of fan service to an already superb film.

So not much in terms of theory with Kick Ass. But that's the point, I guess. Batman can brood, Spider-Man can sulk.

Kick Ass does exactly what it says.

Tuesday, 23 March 2010

Contrast

Proving rather decisive at the minute is this blog's current film. Since the weekend, I have heard people commend the performances, call the film 'sinister', deride the plot, extols its virtues and despise it entirely. There does not really seem to be any sense of middle-ground upon the film - this must obviously mean it is doing something right. Current XBox 360 release Deadly Premonition seems to also be doing the rounds in a similar love it or hate it manner. What most people do seem to be in unison over is that the subject matter is certainly at the darker end of comedy - but is it too far?

I Love You Phillip Morris (2009, Europa Corp.)

It is fairly safe to say that Carrey has never been a star who has been involved in what Richard Dyer would consider the personification of roles. He is an actor who has constantly tried to defy expectations, whether confounding fans of his earlier madcap roles by playing tragic comic figure Andy Kaufman, or delving into bizarre mathematical premonitions in The Number 23 (although it is suspected that this role was maybe not his own choice.) It has become more and more convoluted to know what to expect of a role that Carrey takes. Here, his Steven Russell has once again contrasted opinions - some have likened this to another Eternal Sunshine, or Man on the Moon. Others, such as yours truly, believe that the blackness of the comedy in the film show the twisted, subversive Carrey of his earlier work.

McGregor is much easier to understand.

Aside from his turn as the legendary Obi Wan Kenobi, McGregor has always been, in one way or another, a PRETTY actor. Even when playing the drugged up Renton in Trainspotting, McGregor was at the forefront of the I-D 'Heroin Chic'. So it makes much more sense for him to step into the role of a damsel-in-distress, an object of to-be-looked-at-ness.

Wait. A male actor fulfilling Mulvey's femenist theory? Or is this more symptomatic of New Queer Theory?

Perhaps his role is not so simple.

What stands out (apart from one particular sequence to be discussed later) is a dreamy gaze shot of a blonde, Life Less Ordinary-esque McGregor looking down upon the camera with the sun framing a sort of halo around him. It's clear that he is represented in a manner once afforded to only female characters in Classic Hollywood films, and as one (female) colleague of mine mentioned, he has to reduce his character to that of the simplistic 'damsel in distress'. It's an interesting concept, in that it works, and an audience, gay or straight, can see something romantic, and desirable in Morris' representation.

So what is most striking about I Love You... is that it's not a comedy that makes fun of the concept of 'gay.' Carrey's role is amusing because it is not his 'gay-ness' that is being laughed at, but his flamboyancy, his selfish, materialistic nature. Without wanting to run the risk that Tom Ford met with his response to A Single Man as 'not a gay film', this is certainly a comedy that can appeal to gay or straight alike, as the central concept is something that any person can relate to - unrequited love.

So what of that humour then? Once again, it may be wise to warn of spoilers, in as much as an (albeit twisted) biopic can contain spoilers.

The big taboo of the film is its AIDS moment. Is it still unacceptable to laugh at AIDS? It certainly seemed to be so in the cinema, and some critics have called the moment 'questionable.'

Some context.

Played entirely seriously is a sequence where the audience is firstly introduced to a horrendously gaunt Russell (Carrey - via The Machinist), lying down for effect to show his topless torso. It's a shocking moment to be sure. The audience is then subjected to a protracted sequence involving a touching phone call between Russell and Morris, non diegetic piano playing as Morris tells Russell he still loves him, a single tear rolling down Carrey's cheek.

The death is offscreen, Morris' reaction to it telling the audience all they need.

And it's a lie.

In voiceover, Russell then explains to the audience how, exactly, to fake one's death via AIDS. And it's shockingly funny. Knuckles were bit in an attempt to not give in, but when Carrey deliberately misses a wheelchair in order to slowly fall to the ground, the taboo was breached, and high pitched giggles emitted.

There are two real concerns with this sequence. In 2010, Springtime For Hitler has been around for forty odd years. Sure, Team America used 'Everyone Has AIDS' as a song, but this was more a dig at Rent, and its 'social relevance.' AIDS has not been used, to this reviewer's knowledge as a source of comedy, and it felt like a real barrier was crossed. The other problem is that the real Russell ACTUALLY DID THIS. How else to portray this in filmic terms? How to show the depths to which a man without any morals will actually descend? The only answer is to laugh.

Looking back upon this writing, it seems as though I'm actually heralding I Love You Phillip Morris as some sort of turning point that will be studied in later years. Perhaps it will be mentioned, as part of the new gay cinema that is FINALLY being accepted by mainstream audiences, but it will never be as important as the work of others such as John Waters or Wong Kar Wai.

It is really funny, though.

Sunday, 21 March 2010

REVENGE

Revenge is a common theme that runs through many mainstream texts. The Autobots seek revenge against those Decepticons that betrayed them. Jason Bourne seeks revenge against those that trained and betrayed them. Michael Corleone seeks to destroy those that created his monster - ultimately destroying himself.

No more has this been demonstrated by Park Chan Wook - an auteur so infatuated by the concept that he has created his own trilogy based around the concept. Whilst Sympathy For Mr. Vengeance and Lady Vengeance are both fantastic titles in their own right (the latter being my personal favourite movie of the 'noughties' *as I am loathe to call them*) there is really only one film that truly personifies this aspect -

No more has this been demonstrated by Park Chan Wook - an auteur so infatuated by the concept that he has created his own trilogy based around the concept. Whilst Sympathy For Mr. Vengeance and Lady Vengeance are both fantastic titles in their own right (the latter being my personal favourite movie of the 'noughties' *as I am loathe to call them*) there is really only one film that truly personifies this aspect -

Oldboy (2003, Egg Films / Tartan Asia)

I do wish to mention here that there are spoilers for the film.

I should probably preface this review by stating that this was the film that spurred me onto my Masters degree, and the specific one that caused me to look at Asian cinema, in particular. Oldboy intrigues me on many levels.

First, and most notably, the concept of the 'time passage' is incredible. Oldboy is particularly Korean in what it chooses to showcase, immediately disctancing itself from a wider audience. The elections, the World Cup are shown, images that are particular to a Korean, rather than a Global audience.

How does a Western audience make sense of this? The World Trade Centre? Okay. Oldboy is not entirely Korean-specific in its intentions, but what it does do is highlight a trend in all of us.

Freud has explicitly linked the concept of Guilt to Revenge in the past, but what Oldboy does is play with this. The 'victim' is the guilty party, the enforcee an 'unlucky' overseer. Or is this the case? Oh Dae Sun immediately repeats what he saw to his audience, making him complicit in Woo-Jin's incest.

It's a difficult subject, on many levels, and one I don't feel Park particularly nails, despite the many visual 'wins' of this movie.

Woo-Jin's sister's suicide, in particular, is afforded no real sense of cinemnatic triumph, or importance. And indeed, when Oh Dae eventually cuts his own tongue out in a sense of catharsis, it is as 'matter of fact' as his initial eating of a live squid (something far more shocking to a Western audience)

So where does all of this leave Oldboy? It is technically accomplished, to be sure, but it seems to be lacking in that SOMETHING that creates 'GREAT' cinema. It is lacking in heart, and this is the great irony.

Park Chan Wook eventually created 'I'm A Cyborg...' a film about responding to the world in a robotic, non-natural way. Ultimately, in this film, he hit more upon human nature than in his own revenge trilogy.

Let Oldboy stand as a film triumph - a destruction of narrative, and of representation. But let's not forget that it does not represent the best of a film-maker's career. As The Departed is far more cinematic than Goodfellas, let's not expect that directors peak too early.

Saturday, 20 March 2010

Elliptical

Despite having literally returned from seeing I Love You, Phillip Morris, I've had a movie stuck in my head since viewing it last night that must take precedence over it. It's no secret that I am not a fan of films normally labelled 'twee', and despite being a fan of the author's other work, I immediately dismissed this as pretentious nonsense. Finally, last night I was persuaded to sit down and watch it. The film was a bit of an eye opener.

Synecdoche, New York (2008, Likely Story)

The story of Caden Cotard was something that I thought I had figured out long before I saw the film. After all, as an English teacher, I knew what synecdoche was (and how to pronounce it!) So I must have had an advantage on the audience.

Fast forward to roughly 11:45pm last night, when I turned to my girlfriend and uttered the following (word for word):

"I like it. But I don't know what happened."

The next thirty minutes were spent delving into the murky world of the internet, frantically searching for something to hang upon the film as the documented truth.

First mistake. It's not there.

Primarily, what Synecdoche has done is thoroughly put me in my place. Because of my background, having studied Film and TV theory at Glasgow University, the past few years have had me living my life as a 'oh my, I am definitive in my knowledge of film, aren't I?' Last night's viewing made me realise that in terms of a wider film knowledge, I really know nothing. I understand how narratives are constructed, but when these are played with, I'm as clueless as the rest of the audience. So before I continue, let me say thank you to those internet bloggers out there with a great deal more knowledge on (particularly) psychology than myself, and I apologise for plundering their work and posting it on here.

So, it turns out that Caden is a narcissitic hypochondriac. Because of Kaufman's insistence of downlplaying many aspects, keeping homes looking like homes, and having real problems worry his characters, the film inititally sets its stall out as 'REAL.' Of course, the minute a camera lens it pointed at a subject, the truth disappears. News reports can be distorted, representations of interview subjects through positioning, lighting and costume can change the nature of their words. Kaufman is more than aware of this. The world of Cotard's New York is no more authentic than that of Peter Parker's. Cotard, as the protagonist views the world in his own insular, self-centered view. This means that his 'illnesses' are literalised upon the screen for the viewer, perhaps creating a false sense of sympathy.

It is only when the film shows one of Cotard's lovers, Hazel, buying a new house that something is flagged as wrong. The house is on fire, you see. And Hazel is aware of this. By buying the place, and being aware of her own mortality, Hazel is setting herself out as a contrast from Cotard. Whilst he is trying to fight his own death, she is willingly accepting it, and as such, has become more human. Kaufman uses the mise-en-scene of the characters' houses to literally show their condition. In hindsight, it is far more obvious why Cotard's sink breaks, injuring him. This is not a 'real world incident', it is the film itself punishing him. The 'real world' falling into conflict? Cotard fighting with his own mortality, his brief time on the planet, wanting to triumph.

Without spoiling the rest of the film, it is clear that Kaufman either relishes or struggles with the difference between a filmic life and real life. In Adaptation, he placed 'himself' into the film, and credited it as by himself and his fictional twin brother. Here, Cotard's Simulacrum play becomes real life, or real life is upstaged by it. Or something. It's never quite clear what's going on, nor is it meant to be.

So what is the message?

Ironically, the true meaning, or message, or point of the film is an explicit part of the Simulacrum world (Kaufman explicitly shows the sprinklers creating 'rain' during it.) As a fictional oration to a 'real-life' death, it is the most explicit, manipulative, cinematic part of the film (Gospel choirs anchoring this as 'SERIOUS'). It all becomes clear that this is one merry jape. But wait, what's that... Cotard is a SYNDROME, as well as a name. Right, what does Wikipedia make of this?

The Cotard delusion or Cotard's syndrome, also known as nihilistic or negation delusion, is a rare neuropsychiatric disorded in which a person holds a delusional belief that they are dead (either figuratively or literally), do not exist, are putrefying, or have lost their blood or internal organs. Rarely, it can include delusions of immortality.

The link to Caden cannot be more specific. And that buzzer saying 'Capgras'? What an odd name. Wait...

The Capgras delusion (or Capgras syndrome) is a disorder in which a person holds a delusion that a friend, spouse, parent or other close family member, has been replaced by an identical-looking impostor.

This IS Simulacrum.

It gets confusing. Is Kaufman opening his soul, projecting his own real fears upon the film and Cotard - who claims he wants to make something fantastic before he dies. He is as much an artist as Kaufman, someone obsessed with getting the right representation of 'life' onscreen. Or is this once more all part of the joke?

To be honest, I don't think I am in the right profession to offer any answers to this. Ironically, the best person to answer the question may be the most comical in the film, Hope Davis' Madeline Gravis. This is less a film, than a psychological treatise.

Or is it?

Aaargh. You win, Kaufman.

Friday, 19 March 2010

Butler

Hmm. Looking at posts, it seems that there's a lot of love going on here. Probably time to rant.

Without a doubt, the two worst films of my recent memory have been connected by one obvious link. They both starred Gerard Butler. It probably makes sense to tackle the two of these together, as they are also identical in style, tone and sheer unpleasantness. Without further ado,

Without a doubt, the two worst films of my recent memory have been connected by one obvious link. They both starred Gerard Butler. It probably makes sense to tackle the two of these together, as they are also identical in style, tone and sheer unpleasantness. Without further ado,

Gamer (2009, Lionsgate)

Law Abiding Citizen (2009, The Film Department)

For some reason I always thought that I liked Gerard Butler. He was in 300, he voiced the Black Freighter's doomed sailor, and even managed to be mildly charming in Dear Frankie. Maybe it was the Paisley boy-dun-good aspect of his career. I'm not sure. However, with this week's release of The Bounty Hunter, Butler has certainly managed to carve out a niche for any casting agency looking for a hunky misogynist.

When Gamer was first announced it was hoped that it would somehow manage to catch the link from Film to Games that has never quite been created. Perhaps the protagonist's name (Kable) in some ways reflects that. Then they went and cast Dexter as the villain - amazing! Hopes were high in September when I and a fellow teacher plonked ourselves in front of the cinema screen to view.

Fifteen minutes into the film, I turned to my colleague to give him a 'look' signalling my disgust, shock and general awe that this film exists as it does.

He was already making the same face.

The real issue with Gamer is that it wants to have its cake and eat it. The fast, frenetic editing and buckets of gore appear to be screaming 'LOOK, IT'S JUST LIKE GEARS OF WAR', while with its other hand, Gamer slaps its target audience in the face for daring to play such obscene titles. The most shocking use of this representation is an odious sequence involving an obese, peverted gamer, manipulating a 'character' to fulfil his own fantasies. Are all people who play video games still characterised as fat, weird loners?

After stabbing itself in the face for a while (more on this later with Law Abiding Citizen) with its ham-fisted approach to videogame culture (although from what I've heard, they were too light on their Playstation Home world), Gamer finally devotes some time to Michael C. Hall, the one shining light in this film. His character, idiotically named Ken Castle (is it a reference to his empire? Kuturagi? Or are these too clever for this movie?) is given a song-and-dance number at the film's climax. Watching Hall acting as a marionette whilst singing I've Got You Under My Skin to his game-star Kable is hardly going to win any awards for subtlety, but it is filmed stylishly, in a Chicago-esque black room, and Hall is clearly relishing it.

Then it's all downhill again. There's some child-threatening, and it reaches its bloody end.

That's where Law Abiding Citizen begins.

Opening with one of the most horrific torture/abuse scenes commited to mainstream Hollywood film, it was probably not the best film to take my girlfriend to. But wait, this was all to provide sympathy for Butler's Clyde Shelton (lol) a man LET DOWN BY THE SYSTEM. So, as is common now, he begins a one man vigilante mission to wipe the government out.

Perhaps its telling that this style of revenge - violence flick is in vogue at the minute. We're in a time of great distrust for politicians, and figures of authority - sounds a little like the early 70s, doesn't it? And that brought The Godfather, Dirty Harry, and Death Wish.

But this was 2009, and what once was shocking is now standard. Where to go from there? I'll tell you. If you've ever wanted to stab someone in the neck with the t-bone from a steak while obnoxious noise-metal plays, then lie down while covered in their arterial blood, Law Abiding Citizen is the film for you.

What's catastrophic about the film is that it is even more confused than Gamer. Why set Shelton up as an anti-authoritarian rebel, then try to make the audience support Foxx's pathetic Nick Rice, trying to take him down? The film ultimately decides that authority is preferable, and Shelton suddenly becomes a trained assassin, educated by the same system that he is attempting to tear down. This nonsense, which (no doubt) the director will have intended as ambiguity then makes the opening of the film even less forgiveable. There is no class to the confused morals of this film, ones that have been better portrayed in films like The Dark Knight or Funny Games.

Where does this leave Butler? As mentioned, he's currently slapping Jennifer Aniston around onscreen - and he's supposed to be a sex symbol for females. Butler has fallen into the old Scottish stereotype of the 'Hardman'. Both Kable and Shelton are cliched soldiers, clearly feeling that the end justifies the means.

Butler is set to star in Ralph Fienne's Coriolanus - as Tullus. That'll be a welcome change of pace for him. Wait, he's the one who kills Coriolanus, isn't he?

Oh well.

Thursday, 18 March 2010

CRIME!

So WHY DIDN'T IT WIN?! This was the general consensus after I, in my usual bluster, persuaded everyone that not only would Avatar win best picture (comes down to finances, see) but that the only candidate for grabbing the Best Foreign Film Oscar was a Mr. Michael Haneke. Yes, that's how accurate my prognosticating tends to be. Nevertheless, albeit an attempt to cover my (flat up) incorrect guessing, I still maintain that we wuz robbed.

The White Ribbon (2009, Artificial Eye)

So much has been said about The White Ribbon that it is incredibly hard to know where to begin. Is it an allegory of the conditions that led to WW2? Haneke has gone on record as saying it surely is. The problem with Mr. H is that it is hard to know where to begin and where to end with him. He has never, in his filmic career, given his audiences the whole truth. And he revels in this. To Haneke, the camera's gaze is his license to lie, manipulate and distort the truth. Once the audience is one step removed from the truth, they should be lied to, or at least have to work for their reward. And Haneke makes his audiences WORK.

In The Piano Teacher, we never quite know what leads Erika to her sadomasochistic desires. Something to do with her father, we gather, but are never truly told. Funny Games causes us to question what is actually going on. Are Beavis and Butthead in charge of the movie? Is Haneke? Are we? And then, in his most interesting film, Hidden (Cache), Haneke causes us to question what it is that we've actually seen. Was it the film? Was it another film? Is it real? What in hell is going on with that final shot?

So, Haneke is a bit of a cad.

Where does that leave us then? How to approach The White Ribbon, knowing that this a director who plays not only with what we see, but how we see it, and how we should interpret it?

The first step must be literal, surely. The first problem must be that our main characters are not given names. GOD THERE HE GOES AGAIN. So - the school teacher perhaps represents the hop of Germany saving itself, the naivety of youth and such.

Why then, is it that the children are named? Is it to make their importance more important? Or the opposite - are they simply one offs, not symbolic in any sense. It's clear at this point that Haneke isn't going to offer any answers, so it is up to you, dear reader. (wizard) #reference

Who commited these acts? At first glance it may seem obvious - that it is the children. Then one must rememeber that it is possibly Haneke himself who left the videotapes on the doorstep in Hidden. Does this then mean that he is manipulating the past to explain the rise of Naziism? Does this film have anything at all to do with that?

To top it all off, he makes the audience sit through two and a half hours of black and white film, with performances that are deliberately made to seem as though they are from the early twentieth century. Why make them work for your movie, Michael? Surely the source material, the message or both, are enough.

No, is the solid answer. This is a film about the rise of Facism. This is a film that explains how the most horrific events in human history came to be. The black and white, the performances, the subject matter - they all set in stone the truth. This event was inevitable - that humanity's worst elements would one day be unearthed and displayed for all.

By creating his film in the way he has, Haneke is putting his hands up - the capacity for evil is in all of us. We simply need to choose to do right. He has chosen not to in his film, and the consequences are clear. Characters are written out, endings are not resolved. It is similar to the fate of many from 1939-45, and a sober reminder that we are not that removed from the past.

Horror!

I was going to make this a post about French horror-trauma Martyrs, but since I'm not fully comfortable I've written about it in a sensitive enough way, and since I've just given my mother the link for this, I've decided to switch focus and put on a piece I started writing a couple of weeks ago, during the Glasgow Film Festival. It's still about a horror film, so hopefully that will appease Mr. DS, eagerly awaiting some Martyrs talk.

Frozen (2010, Anchor Bay)

I should probably preface this by stating that I love horror, in all forms. This is probably rather odd for some to hear, as I was a perpetual nightmare-having, couldn't-finish-a-Point-Horror youngster. Still, I'd reckon it was after watching the first Halloween that I realised these were GREAT. The first I saw in the cinema was when I managed to sneak into the R-rated Scream 3, and I remember thoroughly enjoying it (and feeling ultra smart that I knew who Jay and Silent Bob were when they made their cameo!)

My girlfriend, on the other hand, is not the biggest fan of these. I've managed to coax her into watching Rec, Paranormal Activity and Drag Me To Hell, and although she's beginning to enjoy them, she's still reluctant.

Yet it was she who recommended Frozen to us, the newest film from Adam Green (of Hatchet fame). It had gone down a storm (pun intended) during the Sundance Film festival, and she was intrigued by the prospect of the single location story.

This has been attempted before - most notably the lying Phone Booth. The trailer certainly promised that all the action would take place in and around the solitary booth - a tantilising prospect - but it seems that at the last second the makers (or Schumy) had a change of heart and tacked on a pointless side-narrative, one that completely broke the tension of the moments of Farrell-lockage.

So perhaps the first thing to say about Frozen is that it is honest. It really does ALL take place in and around that solitary skilift.

And it's not boring!

That being said, the three protagonists are really a faceless mob. There's a womaniser (who JUST WANTS TO BE LOVED) and the ex-stoner who has made a fresh start with his new girlfriend. And (of course) the girlfriend is interrupting their bro-making-snowboarding trip. So far, so trite, right? But this is all part of the cleverness of Frozen.

By initiating the narrative with stock characters, and labelling itself as a horror film, Frozen has set out its stall rather obviously. Yet most (not all) of the horror comes from the three of them up that ski-life, scared for their lives. Frozen cleverly subverts the traditional horror trappings of 'your worst nightmare' by going all Lord of the Flies on the audience. The horror, the fear, the Beast, is what is initially inside each of the characters. It is genuinely unnerving to see these characters laying into each other as the lift breaks, and they have no one but each other (themselves?) to blame. As they eventually reach a strategy on how to escape, male bravado manages to prove the undoing of their plan. Again, Green lays on that it really is their fault that they are up there, making the audience question their support of these characters. And as the plan goes from 'OH GOD NO' bad to 'unnecessary villain' horrific, it is unclear whether we really want these characters to survive, or to prolong their horror.

The most horrific parts of the film are actually the natural terrors. The steel ropes eating through gloves, the skin tears as a result of frostbite - these are the moments that really had the audience on end. These things are natural horrors, graphic ones at that, and they really resonated with the crowd. Using actual injuries as horror 'gore' is incredibly clever.

Sadly, the appearance of 'villains' (avoiding spoilers!) does take the movie into slightly conventional territory. Thankfully they're not what you'd expect of horror baddies. But, still...

My biggest complaint of the film (which I thoroughly enjoyed) is that I don't think Mr. Green went far enough. Send a group of rich, selfish Yale graduates, or benefits cheats up that life next time, and let them squeal. Then watch the cash rake in.

You can send me my royalties via paypal, Green.

Horror!

I was going to make this a post about French horror-trauma Martyrs, but since I'm not fully comfortable I've written about it in a sensitive enough way, and since I've just given my mother the link for this, I've decided to switch focus and put on a piece I started writing a couple of weeks ago, during the Glasgow Film Festival. It's still about a horror film, so hopefully that will appease Mr. DS, eagerly awaiting some Martyrs talk.

Frozen (2010, Anchor Bay)

I should probably preface this by stating that I love horror, in all forms. This is probably rather odd for some to hear, as I was a perpetual nightmare-having, couldn't-finish-a-Point-Horror youngster. Still, I'd reckon it was after watching the first Halloween that I realised these were GREAT. The first I saw in the cinema was when I managed to sneak into the R-rated Scream 3, and I remember thoroughly enjoying it (and feeling ultra smart that I knew who Jay and Silent Bob were when they made their cameo!)

My girlfriend, on the other hand, is not the biggest fan of these. I've managed to coax her into watching Rec, Paranormal Activity and Drag Me To Hell, and although she's beginning to enjoy them, she's still reluctant.

Yet it was she who recommended Frozen to us, the newest film from Adam Green (of Hatchet fam). It had gone down a storm (pun intended) during the Sundance Film festival, and

It begins

I figured it would be sensible for me to start a film blog some day - after all, I do enjoy the things, and they're part of my own educational background and my job.

What I'm hoping to do here is simply post every so often on films that are either newly out, or that have popped up on my radar again.

I'm going to start by looking at one of my all time favourites -

What I'm hoping to do here is simply post every so often on films that are either newly out, or that have popped up on my radar again.

I'm going to start by looking at one of my all time favourites -

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001, Universal)

It was actually my sister who got me into Wes Anderson, as she made me sit down and watch Rushmore one day. I only ever caught up with his entire back catalogue last year, having finally taken the plunge and picked up Bottle Rocket (for £3, no less.)

I've loved everything he has done, which is rather odd for me, considering that other 'twee' filmmakers seem to do nothing other than pester me. I've hated Juno, Amelie, and Ghost World, among others. And yet, Anderson's films always have some element of charm, whether it's the 'not quite leftfield vintage soundtrack', the immaculate mise-en-scene, or just that he keeps putting Bill Murray into everything. I'm pretty sure he's not done a 'bad' movie.

Of course, Anderson's style owes as much to his long-standing cinematographer Robert Yeoman as anything else, and he perhaps sells himself as an auteur by his long running use of 'family and friends', but nevertheless, the man has an eye for films about families.

As long as they're dysfunctional, that is.

In this sense, Tenenbaums is his Magnificent Ambersons, focused entirely on a family (his others tend to look primarily at parental issues) with each character flawed, yet entirely likeable. No where is this more apparent in Owen Wilson's Eli Cash. A drug user, rich, vain, sleeping with a Tenenbaum for his own satisfaction, Cash is still more a sad, lonely figure than anything else. He desperately tries to hold on to his own American dream, believing he can truly have it all. His costume, with a dapper cowboy hat, seals this representation.

And we like him.

Sure enough, when he starts mentioning 'Wildcat' and destroying weddings while emblazoned with face paint, we know exactly why he does what he does. He only wants to be part of the family.

It's not just Eli, of course. In the years since, websites such as Tenenbaum FAIL have provided many-a-lol from the disenfranchised followers of Anderson's films, who strive to dress exactly as 'oh God she's so moody Margot' or 'oh God he's so moody Richie.' What these people fail to realise is that the characters are more than their perfectly established rooms, or their striking costumes. Dressing as a Tenenbaum does not make you one. In fact, as much as we long for the world of Archer Avenue, it should stay where it is - as something to be looked at. Anderson's world is so perfectly created, so nuanced, one can understand why people wish to be there - simply look at recent Avatar-related events (PANDORAAAA!) Ultimately, though, these people, these problems are something that only exist in film, and the wonderful thing about watching The Royal Tenenbaums is the realisation that they can only survive in Anderson's well created world. The real world, with ACTUAL ISSUES would be too much for them, and they'd probably all end up locking themselves in their bathrooms.

So let the Tenenbaums stay in the film, and let the film serve as a strong reminder that there are still great storytellers out there. With Fantastic Mr. Fox, Anderson pushed himself from Indie-auteur to the spotlight (as Spike Jonze did with WTWTA). His next film, My Best Friend, is a remake of a French comedy - something that sounds far more at home with someone like Margot Tenenbaum.

Whatever he goes on to next, I shall always have those fond memories of late 2001 at the cinema, enjoying the most bonkers, lavish, and well crafted cast of characters I have seen in any film to date.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)