For the past few weeks, I have put over 40 hours into Fire Emblem: Three Houses. This in itself is nothing new or surprising - since discovering Awakening on 3DS, I have completed every game in the series, including all three pathways in Fates. Clearly, Fire Emblem is a series that is close to my heart.

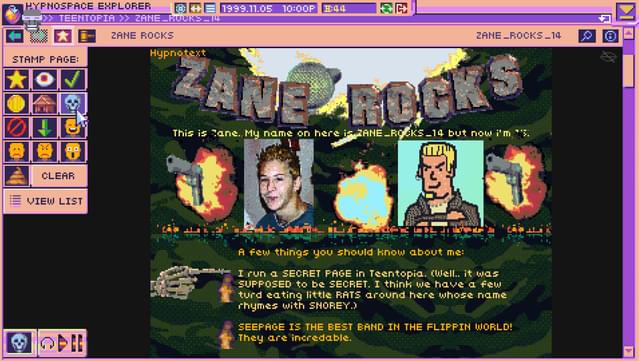

At the start of 2019, however, I was also hooked on another game - one that has resonated even stronger with me than Fire Emblem ever will - Hypnospace Outlaw, perhaps a lesser known title, which is available on the Steam service on PC. Hypnospace is a game that I still think about - perhaps not on a daily basis, but certainly weekly. In many ways, it was a game tailored to my own age and demographic, in addition to my own online history.

In exploring both of those games, and by subsequently noting elements of these titles that resonate through other games I have enjoyed in the past 15 years, namely: Phoenix Wright, Virtue's Last Reward, and Persona 4: Golden, I have come to a stark realisation.

I really like visual novels.

(Hypnospace Outlaw, 2019, No More Robots)

(Fire Emblem: Three Houses, 2019, Nintendo)

In all of the titles mentioned above, there is a different mechanic with the way in which the player navigates the game; with Fire Emblem, your character engages, between discussions, with turn based combat with a multitude of enemies; in Hypnospace, you are surfing, and sleuthing, an alternate reality simulacrum of the internet, circa 1999; Phoenix Wright sees you making choices of evidence / conversation topics to win defence cases in court; Virtue's has your protagonist solve fiendish escape-room games in order to progress, and in Persona, the dialogue is couched within a massively-scoped role-playing game, requiring grinding (see previous posts) and careful choice of battle mechanics.

All of these games, however, use the trapping of a variety of different genres of titles that all fold back into one - the visual novel.

Popular mostly in Japan, the visual novel is as literal as its title suggests - that the narrative of a story will unfold with character reactions or settings to represent what is described. These can vary from the absolute mundane - a character's day at school, as in Persona, to romantic choices, to stories that carry elements of pornography in their descriptions.

Perhaps to call this a 'genre' is a misconception.

What visual novels allow, is an element of author control that can often be missing in other titles, such as open world-games. Imagine a Grand Theft Auto where you are told on your screen that "Trevor walked in to the bar and sat and had a drink".For any players of the game, this is absolutely one of the things that Trevor may do. However, Trevor is also a psychotic, unhinged character, one who will murder for fun, and is supposed to be the player's cipher for whatever mayhem they may wish to unleash. The visual novel works when there is a story to be told, and the player may have some (note, some)agency as to the outcome, but these endings are set in stone.

And yet, I play through a number of titles, including GTA, Assassin's Creed, Watch Dogs, Saint's Row, all open world games, despite enjoying, and preferring the authored content. The reason for this is I love an ending. I love to see where the game will take me - how will my murderous character ultimately finish the game?

In a previous post, I discussed the ending of the game GTAIV, because I believe the pathos of the finale made the rest of the game important. Every decision your character made, led them to one of two outcomes, one I believe to be more important than the other. I am a huge fan of authored content, and enjoy following the journey that creators take me. It may be time for the admission (and absolutely not humble-brag) that I have never played Minecraft as I did not see the purpose of it, and bounced off The Sims, although with a slower curve, because I could not see the end point.

The visual novel is exciting, because, as mentioned, the trappings around it can appeal to a number of different type of players. What I like most around it, much like good cinema, is following the vision of a creator. I want to see where they feel the characters should go, and, if I don't agree with this, to be able to at least have a concept of their journey.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58448459/MonsterHunterWorld_3_1.0.jpg)